The original Fallout begins with a series-defining vicissitude: a bomb shelter that can no longer purify its water. So it stands that someone, invariably you, has to venture into the ruins of the outside world in search of a complex component to set the life-giving machinery in motion again.

Without a Water Chip, Vault 13 will be running on its reserve fluids until a new one is located. Seeing to your exit from the blast doors that bulwark Vault 13’s inhabitants from the outside world, the Overseer estimates that, with careful rationing, the remaining water will last about 150 days before certain desiccation followed by exodus or death. “No water, no Vault,” he declares. Their hopes rest squarely in your efforts; so begins a journey that’s always on the clock.

This kind of deadline-marked gravitas is a common enough dramatic mechanism to kickstart a game with. Usually, it amounts to nothing. In other Fallout games, you can fuck around no matter how pressing the stakes and Father Time will do naught but patiently stroke his beard for weeks or months on end. But this time, the Overseer – and by extension, the game’s designers – aren’t just fucking around. Check your Pip-Boy, and the interface communicates in no uncertain terms that you have 150 days to go outside, find a new Water Chip, and then hightail it back before the Vault’s water reserves really do run dry. As you travel to the nearby town of Shady Sands, it ticks down. Those 150 days become 148; 148 quickly becomes 140. Any assumption that all of this is just an elaborate display of urgency-instilling histrionics begins to fade, and before long, that timer begins to tick as surely to your own death as the death of everyone you’ve ever known.

The unembellished realness of this timer hits hard – the first question new players seem to lead with is how bad it is, or whether it can be turned off. It’s easy for someone without much CRPG experience to assume that it’s always ticking, which thankfully isn’t the case. Most interactions exist in stasis, from running to fighting to talking. No time passes while you shop in Junktown or The Hub. Some interactions, such as waiting until nightfall to continue a quest, are the natural exception.

Edit: A friend pointed out that time does actually pass while walking about, but that it does so in real-time, making the effect so slight that you’d almost never notice it. Still a fun wrinkle, since you could technically spend a few extra minutes fucking around only to discover that a shop closed in the meantime, or just watch the time of day change. These interactions are doubtlessly rare, but it’s neat that they can happen.

Anyway, it suffices to say that having 150 real days to save the Vault doesn’t necessitate much worrying; you can easily beat Fallout in less than 24 hours. Bum around to your heart’s content.

Where the hourglass really drains, however, is on the map. Travel takes place on a gridded atlas depicting the sprawling desolation between named locations, casting you as the red Indiana Jones line bouncing between them at a sickly pace. It abstracts the trek from one place to another through implied conditions, random encounters, and the ceaseless march of hours and days, only periodically interrupting so you can see what a miserably shitty time you’re having. You might have to stop to fight something, or search for water while suffering the consequences of dehydration. All of this takes time.

There’s a layer of strategy to getting from place to place as quickly as possible. Running the circuit from Vault 13 to Shady Sands to Junktown et al. can easily take more than a week, particularly if you’re using the built-in pathfinder to travel the smallest distance between locales. This reveals that not all map squares are created equal, and while walking through a square of desert might take ten hours, the same distance could easily take twenty once you’re cutting through mountainous terrain. Suddenly, the impending timebomb of Vault 13’s water supply seems palpable; a selection of bad routes could inexorably detonate it. Exploration must be undertaken thoughtfully.

There’s also the necessary commodification of your finite time, sometimes requiring you to nervously approve its exchange for money or supplies. Once you reach The Hub, you can start jobbing with caravans for caps (cash), safeguarding their journey from one place to another. Their routes can stretch out for more than a week, but even the availability of the job can sap the same amount of time. The worst-paying caravans leave the most often, but those with the highest pay will only leave twice a month. Is it worth the wait? If you have your sights set on buying necessary supplies, you might really have to weigh it.

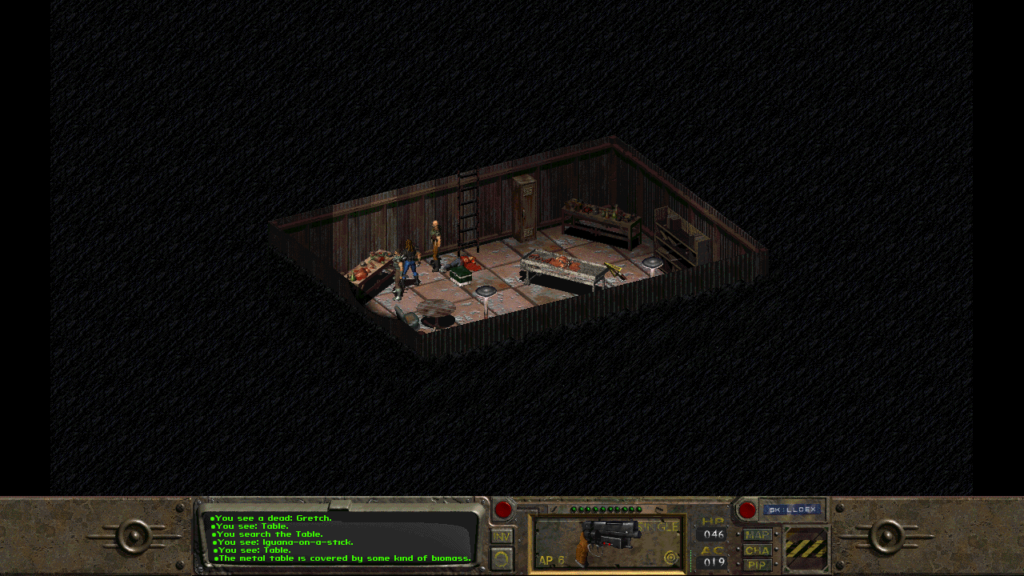

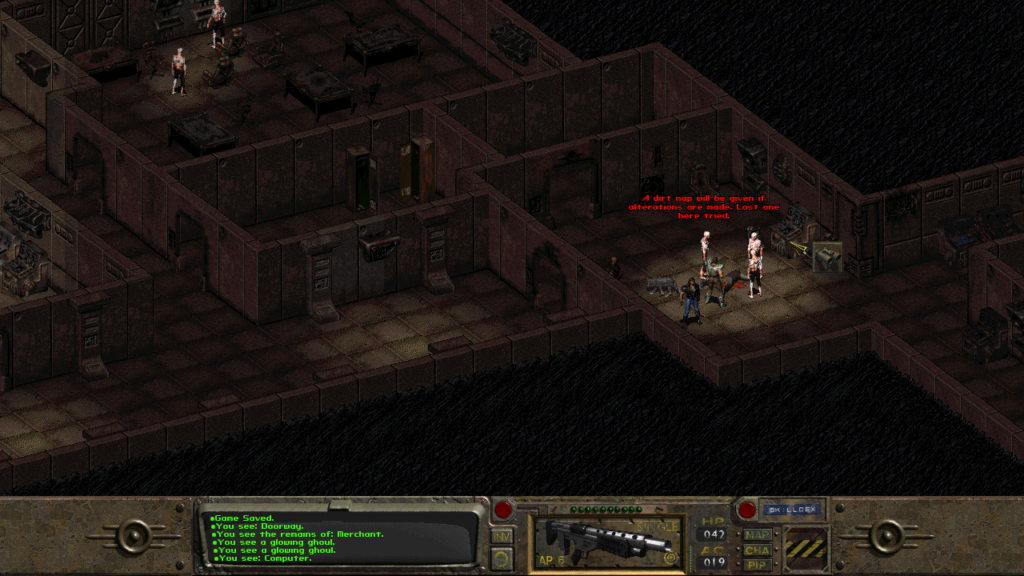

This encroaching, ever-present anxiety of certain doom is one of Fallout’s strongest emotional qualities. Wandering around Necropolis, sneaking past rotting ghouls and hearing Mark Morgan’s unbelievably despairing soundtrack, thinking about the Vault 13’s remaining days upon the Earth, it’s hard not to feel awash in something beautifully morbid; the interactive equivalent of listening to Dead Flag Blues past midnight. Fallout‘s timer is a brilliant conceit.

But…

I would write something like this to convince an audience that Fallout‘s time pressure is, in concept, meaningful. In actuality, my description of the timer as a source of stress and dread might only serve to baffle anyone who’s actually played it. This is to say that the timer is meaningful, inasmuch as it really does tick down. It is not meaningful, however, in the sense that you’re likely to feel like anything I’ve described is at any risk of actually happening.

The truth is that 150 days is exceedingly generous – on my first and current playthrough, with little outside help, I saved the Vault with just under 100 days left on the doomsday clock. That was with a reasonable share of mistakes, missteps, and boondoggling. Compared to later endeavors, Fallout isn’t a terribly large game; I find this to be one of its most enduring, endearing qualities. Nonetheless, it means that you’re likely to stumble into Necropolis, where the quest’s solution lies waiting, before the realities of failure can be meaningfully imagined.

The game is full of little moments where the timer, often vestigial, briefly crystalizes into a more thoughtful form. One example comes from the Water Merchants in The Hub. If the timer is starting to breathe down your neck (and you can financially afford the relief), they can be paid to deliver more water to the Vault. This affords an extra 100 days to find a permanent solution to the crisis. But, in doing so, the Vault’s greatest asset – its relative obscurity to the outside world – is exposed to greater strain. After all, The Hub is also where you help a bunch of caravan owners discover that Super Mutants have been jumping their shipments and kidnapping their drivers. The potential risk is clear: more time now, but less time later.

The actual programmatic consequence of this, in theory, revolves around a second timer. When you finish the Water Chip quest, effectively beating the first countdown, a second countdown that’s been quietly ticking since the beginning starts to enter the foreground. Super Mutants are slowly advancing through the region, mutating its inhabitants and conquering their settlements; within 500 days, they’ll have converged on Vault 13, ending the game. Since the water shipments make the existence of the Vault increasingly obvious, the timer shrinks by 100 days, meaning you effectively add to one timer by subtracting from another.

I say “in theory” because, without patches, no Fallout player will encounter this second timer. I’d wager that, in the last 25 years, very few have. A patch released within the same month of the game’s release turned 500 days into 5000, nullifying it. Much of the work associated with this timer, wherein the human inhabitants of various settlements would eventually be replaced by an occupying garrison of Super Mutants, is dummied out in the final release. Combined with the relatively lackadaisical amount of time you’re already allotted, the Water Merchant decision amounts to virtually nothing – at best, a direct exchange of money for the experience you earn by paying them.

Another lost opportunity comes with the quest’s conclusion. After reaching Necropolis, it becomes clear that an entire settlement currently relies on the water purification chip you’re gunning to collect. The town is inhabited exclusively by ghouls, whose rotting appearance and generally cannibalistic intent is designed to repulse. The instinct is to wipe settlement out with impunity. But as a group of sewer-exiled ghouls demonstrate, they’re still people that both want, and deserve, to live. The player has to navigate their potential xenophobia and the pressing needs of their Vault to decide whether the denizens of Necropolis will live or die.

But again, this is merely the ideal version of the quest. The actual choice isn’t much of a choice at all: instead of getting purified water from the machinery you intend to pilfer, the people of Necropolis can just draw it out of a reservoir attached to a (currently broken) pump right next to the area where you’d steal the chip. Fixing it requires a high enough Repair skill, but the game showers you in multiple skill-increasing books right before you make the attempt, ensuring that your prior stat allocations have zero bearing on your ability to solve the problem amicably. It feels like something a modern Fallout game would be criticized for trivializing; the only reason to doom Necropolis is if you’ve set out to do so.

The result is a morally and logistically unchallenging dilemma driven by player convenience; a simple, frictionless outcome to what could be the game’s most difficult choice, driven by one’s onus to a decision in the face of a deadline. Instead, and especially funny for a game wracked by deadline-enforced compromises, time is easily ignored.

This is not a surprising outcome for such a delicate feature. Fallout is a product of the usual culprits: a hectic, hothoused development cycle, wracked by shifting ideas and technology, barely saved from cancellation on multiple occasions, etc. Elements like the SPECIAL system and the entire premise of companions were late or intensely rushed additions. In all likelihood, the timer would’ve never existed at all without lead designer Chris Taylor – “many people didn’t like the time limit, including QA, and claimed the limit made them feel rushed and encouraged to ignore side quests” according to Fallout creator Tim Cain, who later reiterated his dislike for the timer in a GDC talk from 2012. His argument, that it caused players to “miss fun things” in their rush to complete the game, is both totally understandable and somewhat like saying that dying prevented players from progressing. Irrespective of how non-pressing the timer actually is, picking and choosing what to do is the point! If everything locks together, balancing and making those choices is the fun!

In the same source as the above quote about how unpopular the time limit was, Cain says that “Fallout was a rare development environment in that all of the people working on it were in agreement about the kind of game we were making.” Still, it’s hard not to speculate that internal tensions surrounding the timer had something to do with its relative lack of import on the finished game; why work to further hook in a feature your team (and your audience) has little enthusiasm for?

Much is said about videogame friction, itself a dire effort to communicate the necessity of lows to a machismo-addled audience addicted to highs. Few, however, will bat for the time limit as an experiential arbiter outside of Majora’s Mask or Outer Wilds or any such game where the time limit exists as a loop carrying an attached player performance, one wherein repetitious actions are continually polished to the level of maximum efficency. Timers do not, as borders that neither bend nor quickly revert, tend to gather much love, often leading to an immediate capitulation towards player feedback about their restrictive nature.

A surprising number of games begin from, and gradually or quickly shed, a basis of strict time pressure; among others, the original Pikmin comes to mind as a game formulated around a finite calendar that was quickly designed out of most subsequent entries. Even Dead Rising eventually dropped the timer, and Fallout did in record time – the aforementioned patch turning 500 days into 5000 days released mere weeks after the game’s release. Fallout 2 included the same 13 year timer without any narrative significance, likely as a carryover nobody was bothered to fix. By Fallout 3 and all subsequent games it was, of course, long gone; unless you count the FOMO design of Fallout 76, in which case it triumphantly returned in Battle Pass form.

Much has been written about the evolution of the Fallout franchise from its roots to the modern wasteland of franchise-as-theme-park; from a kind of dread-induced, rusting, horror-bent A Boy and His Dog tableaux to a slurry of Fallout-themed imagery driven by anodyne writing (the ending of 3 being the worst exception) helming a stagnant, ever-expanding parody of its own decadence. It must be a larger open-world game than the previous one; it must be a television show; it must be more, always more, until unsold Vault Boy bobbleheads line landfills with all the rhetorical power of a still from a literal Fallout cutscene. Growth – of games, of franchises, of earnings – must occur at any cost.

The obvious culprit is Bethesda, whose custody over the franchise has always been a point of contention. But it’s hard not to see a far more innocuous, immaterial form of this occurring with Fallout 2: a game intended by the suits at Interplay to receive the largest possible return on the smallest possible investment. The result stretches over double the length of Fallout, with twice as many quests, locations, characters… you get the gist. What nobody working on Fallout 2 got was twice as much time to make any of it, receiving something in the ballpark of nine months to make a Fallout the size of Baldur’s Gate.

That it makes no effort to discover an equivalent to the original’s timer is a foregone conclusion. What the timer did, ultimately, was set the scope of the experience. Come rain or shine, Fallout had a set length; whether the team would’ve discarded this idea on their own reconnaissance means nothing if corporate conditions didn’t permit its existence in the first place. Sacrificed to the altar of growth, it and anything cut from the same cloth must die so the cult of more can live. Irrespective of its own successes and failures, it’s hard not to see a seed in Fallout 2 waiting to germinate into the all-encompassing maximalization that would cement its pupation into the open world monolith we glance it through today.

All of this means that Fallout’s timer, for all of its promise, is an illusory pressure – one that neither influences your decisions nor pushes you towards unlovely sacrifices. Its resulting impact is diminished and its potential is discarded, never to reemerge within a process that rejects the very principle of its existence. But like most things sabotaged by compromise and abandoned by capital, it feels like all the components of a stronger version of the same idea are still scattered around, waiting to be iterated on by someone with freedom and, as irony would have it, more time.