If you’ve ever played the original Doom for more than five minutes, you’ve probably gotten into a situation where two enemies start hitting the shit out of each other. This universally beloved feature is called monster infighting, which triggers in most cases when accidental friendly fire occurs. Since it occurs often, this small addition is both frequently observed and perpetually a matter of tactical consideration; Doom is often about starting fights in the hope that something else will finish them for you.

At the core of indiscriminate monster infighting is a conveyed savagery. When you’re faced with the legions of Hell, you’re not dealing with an invading civilization insomuch as a concentrated leak in a dimension of raw malice filled with violent little animals. Cooperation between these creatures is largely artificial – literally and figuratively – which becomes clear given the immediacy under which those bonds dissolve into outbreaks of pain and brutality. Doom‘s essential quiddity is an atmosphere of chaos and terror and blood, and demons see no accidents on the battlefield.

From Doom came Quake, which left this loose system intact; Quake has essentially the same plot with a shift towards Lovecraft-esque stylings, so the idea of an invading world full of indiscriminate maleficence still applies. Quake II derives from a similar base, substituting cosmic horror for a more traditional (boring) army of invading alien butchers. Their implied hivemind seems about as effective as the one Hell was running on, but this fact alone serves to make the Strogg a little interesting: a superstructure rotted away by its own lack of scruples.

Where monster infighting got really neat was in Half-Life, whose novel first-person narrative and imsim-adjacent tendencies provided a framework to portray a number of context-specific relationships. Soldiers attack non-soldier humans on sight, but they also attack all aliens – entire chapters are dedicated to showcasing these fights on a large scale, suggesting the outcome of a wider conflict. More interestingly, while aliens are largely cooperative, there are exceptions designed to indicate ecological predilection towards certain hostilities. One primary example is that bullsquids will always attack headcrabs, and will even ignore you in doing so. Their hatred (hunger?) for the creatures is so ravenous that it supersedes rational behaviour, which can be exploited in the rare moments when they’re pursuing a meal that isn’t you.

Halo would go on to further explore the idea of specific, context-agitated infighting. The disparate races of the Covenant occupy an obvious hierarchy of shitty little assholes (Grunts, Jackals) dominated by an upper commanding class (Elites, Brutes). A lot of their interesting behaviour has to do with the mutability of their convictions and the distinction between their emotions: kill an Elite, and all the Grunts under their command scatter in a panic; kill a squad of Brutes, and the one survivor will go berserk instead of behaving tactically. Every fight becomes a showcase of the comedically awkward instability that results from a stratified empire failing to accommodate the diversity generated by its own conquests.

A notable exception in typical Grunt behaviour can be found in Halo 2, where Grunts allied with the “Heretic” group encountered by the Arbiter are way less prone to running away or freaking out. This is totally intentional and, along with a few other tweaks, serves to communicate how much more well-equipped and respected they are in this particular splinter group. These are Grunts that have chosen to be here, unlike typical Covenant conscripts. They believe strongly enough in the ideals at play to actually put their lives at risk for them.

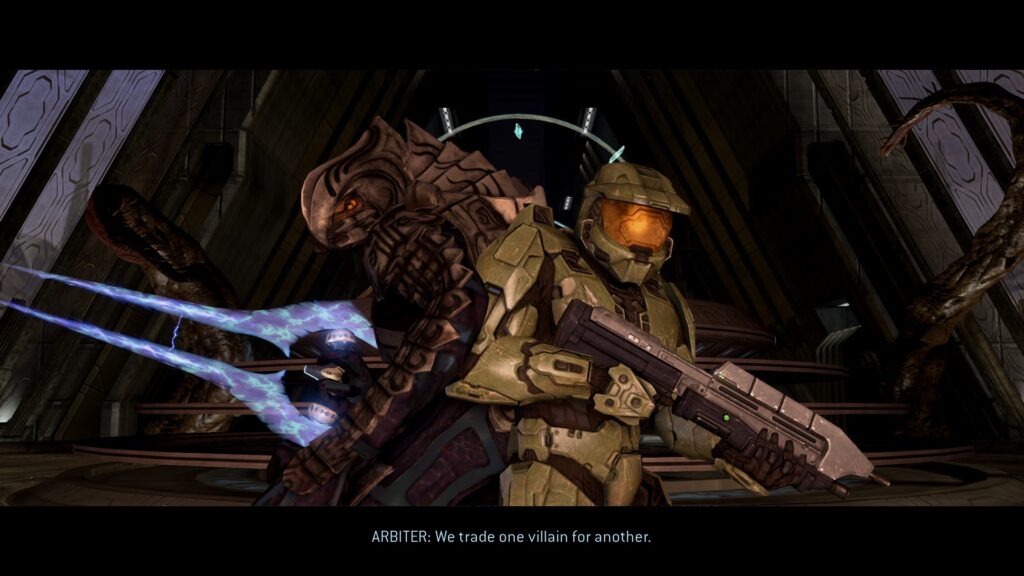

What’s cool about Halo is how this informs the developing plot. When a civil war breaks out between the Elites and Brutes towards the end of Halo 2, the schism feels like a natural consequence of everything we’ve spent two games playing, rather than merely witnessing. Stumbling into their fighting cements the notion that the Covenant, more than a name behind a bestiary, is an organization that can grow or change in surprising ways.

Even the Flood operates on a similar principle. Though ostensibly an intelligent hivemind, most games would contain nothing more than a zombie enemy class whose wider capabilities were relegated to cutscenes and lore material. But in Halo 3, there’s a moment when they even declare an allegiance with you and fight by your side during a (brief) sequence when your immediate goals align. This demonstration of their acting intelligence, and the resulting carnage visited upon your Covenant enemies, is far more unsettling than anything the faction could accomplish in a vacuum.

One could argue that some of these later examples have less to do with infighting and more to do with just, y’know, fighting on a general scale. But I think the core of what I find interesting about monster infighting is developed further in every instance wherein cooperation (or a lack thereof) is rendered fluid. Enemies fight other enemies and, in doing so, literally fight themselves – they can break rank, let their emotions get the better of them, and even shift their tolerances in relation to the plot.

The axiomatic principle of compelling enemy AI is that looking smart requires you to look dumb under the right circumstances. It’s easy to make an AI opponent that’s unassailable in a game of chess, but it’s far harder to make one that feels like it can be tricked, read, or exploited in the same way that a human being can. This requires emotion, which is difficult to convincingly simulate… for a chess robot. Games make this a little easier, since you can record the robot screaming or animate it smashing the table into pieces. Doom simulated emotion by just having enemies indiscriminately attacking each other, which became Half-Life’s gesturing towards a simulated ecology, which became Halo’s cultural and emotional divides, et al.

F.E.A.R. is universally cited as the benchmark for “smart” enemies in a first-person shooter, which belies that a lot of its impact is upheld by decisions that are smarter than the enemies themselves. What really sticks out is the fallibility of these soldiers, who often fire blindly and signal their current state in a yelling panic, screaming commands at each other and generally being little state machines who tell you when they’re throwing a grenade or flanking. When you can ascribe intent to an action, even if that intent is panic or overzealous rage, you’ll usually view that action as intelligent; if it’s not a “good” choice for the enemy to be making, it feels like a human mistake rather than an undesirable error.

It’s a great lineage, but it feels like it terminates (along with infighting itself) roughly around 2005, where F.E.A.R. and Peter Jackson’s King Kong: The Official Game of the Movie (we use its full name out of respect) represent some of the last truly interesting high-profile experiments with simulated behaviour in a first-person shooter. Folks are endlessly surprised when a game like F.E.A.R. goes unsurpassed or even matched after close to 20 years. Unfortunately, the period that followed – and which frequently persists today – is one where spending money and time to find more interesting ways to murder the player is considered a source of poor ROI. A line of successive iterations becomes whatever optimized solution doesn’t rock the boat, and it only becomes harder for any individual person or team to turn back the clock just to do something as well as it was being done decades ago.

I wouldn’t go so far as to allude towards a universal method for designing engaging enemy behaviour, and by extension, a compelling first-person shooter. Concurrently, I can only say that everybody loves when actions contain intrinsic reactions, whether violent or aural or simply emotive. Even in its most primal form, when one demon assaults another, the capacity for internal discord makes for timeless work.

If you enjoyed this blog, you should probably play Rain World!