Everything that needs to be said [about Morrowind] has already been said. But since no one was listening [to what was said about Morrowind], everything [about Morrowind] must be said [about Morrowind] again.

― André Gide

Since getting into Morrowind, I’ve learned that a lot of things are disappointing. Not Morrowind, obviously. Rather, there are a lot of things wearing the skin (and branding!) of Morrowind without any of the internal complexities, revelations, designs, esotericisms, etc. that make it such an enduring, singular work. It’s the worst kind of brilliant thing – once you see it, you see it everywhere, but it’s never even half as good.

I started Oblivion as a chaser to keep the momentum going, which I’d liken to finishing Frank Herbert’s Dune books before promptly cracking open something his kid wrote. Mind that Oblivion is a lot better than that; it’s just a similar feeling of seeing the ground come out from under you in real time, watching as great things become average and average things become outwardly bad. It wasn’t until the jump from 2002 to 2006 that I could truly appreciate what was already in the rearview mirror… including, to my surprise, things I didn’t expect to miss at all.

Take quests, for instance. Morrowind has a lot of quests – roughly 490, none of which are randomly generated in the style of 1997’s Daggerfall. This is a sharp contrast to Oblivion‘s 223~ quests, which is a reduction over half. This seems like a good thing! Oblivion‘s quests are unequivocally more bespoke than Morrowind, whose errands largely revolve around fetching things from caves or engaging in conversational mazes without any of the bells and whistles that came to define future Elder Scrolls games. Quests in Oblivion are filled with voice acting, scripting, and other memorable, handcrafted scenarios. Whether you’re wandering into a dream, stepping inside a painting, or involving yourself in a conspiracy – and if you can’t find one, you’re not looking hard enough – there’s adventure and excitement behind every rock, bush, and suspiciously quest-shaped animal.

Isn’t that what you come to an Elder Scrolls game for? Adventure? If so, why does Oblivion leave me feeling so empty, even when I’m putting down an ancient evil or saving a town? If Morrowind‘s quests seem “worse” by most modern metrics, why do they feel more pleasing? Oblivion‘s approach to quests is unequivocally fun, whereas Morrowind‘s approach seems rote and inoffensive. Shouldn’t quality surpass quantity? Shouldn’t fun surpass tedium?

Each game holds an era-defining philosophy; in detangling it, I found my answer.

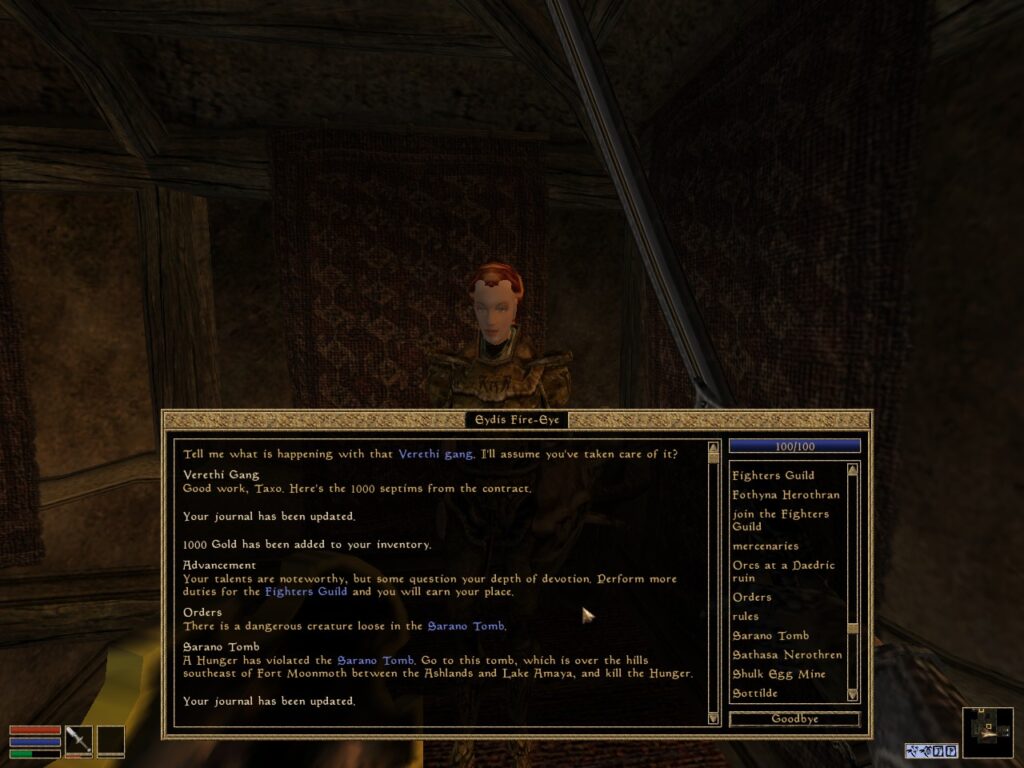

To start, it might serve to contrast an introductory Fighters Guild quest from Morrowind with one from Oblivion, so let’s do that.

Morrowind: Exterminator

- Eydis Fire-Eye tells you to help a Balmora woman named Drarayne Thelas with a rat infestation.

- Upon arriving at her house, she can be spoken with for some additional dialogue, including where all three rats are located (one trapped in her bedroom, two locked upstairs).

- The upstairs room is actually a storage room, and its contents can be easily stolen for some extra cash. This is one of several early situations where a player can do something “wrong” with intrinsic personal benefits and no apparent personal consequence – beyond, of course, the imagined consequence of depriving an innocent person of their belongings.

- After the rats are dead, you can inform Drarayne and then return to Eydis Fire-Eye and receive 100 gold.

Notes: A simple quest with a simple reward. It introduces you to Drarayne – a bit character that’s visibly obsessed with pillows, potentially setting up another funny quest. The rats aren’t much of a threat, though the two upstairs can take you by surprise. You’ll feel embarrassed if they do. It’s okay, I won’t tell.

Notably, this errand offers the ability to rob Drarayne with impunity. Whether or not you take this opportunity isn’t explicitly meaningful and has zero bearing on the quest itself. However, the ability to do something “bad” without an external consequence (and the subsequent question of whether you should do it) definitely shapes a player’s sense of morality. I love that Morrowind doesn’t mark stolen possessions with Red Danger Text, by the way – people won’t magically refuse to buy stolen property, though you should probably still keep track of what you’ve taken. If you’re not careful, the person you stole from can realize that you’re selling their own shit back to them. That’s also pretty embarrassing, and while I won’t tell, that person absolutely will (tell the guards, who will arrest you).

Oblivion: A Rat Problem

- Azzan tells you that a woman in Anvil, Arvena Thelas (probable relation), is having a “rat problem.” However, Arvena refuses to elaborate.

- Arriving at Arvena’s house reveals that she actually keeps rats in her basement as pets. Rather, the “rat problem” is that something keeps killing her rats.

- Downstairs, you discover a starving mountain lion attacking her rats. There’s a hole that allows them to enter and exit her basement, but where are they coming from?

- Arvena asks you to find a local hunter named Pinarus Inventius who can help you hunt the rest of the pack.

- Pinarus Inventius leads you to a small clearing outside of town where a group of mountain lions can be killed. He does this very slowly, so you’re likely to walk ahead and deal with them before he arrives. Pinarus Inventius pisses me off.

- Returning to Arvena has you kill another mountain lion in the basement. After that, she shares her belief that a neighbor named Quill-Weave is responsible for the attacks; she’s never liked Arvena’s rats and has apparently been spotted wandering near her house at night.

- Talking to Quill-Weave leads to flat-out denial, forcing you to wait near Arvena’s house at night to see what she does.

- Quill-Weave is spotted leaving meat near the same hole the mountain lions were using. Confronting her reveals that she wanted to lead the rats out, rather than lure nearby animals in. She asks you to keep her secret.

- Telling Arvena that Quill-Weave wasn’t involved leads to Quill-Weave giving you a small boost in Acrobatics; telling the truth leads to Arvena giving you a small boost in Speechcraft. Either choice completes the quest, and you can return to Azzan for a leveled gold reward (anywhere from 100-600).

Notes: A far longer quest with a variable reward. It’s funny and memorable, but seems a little exhaustive on paper; anything that could happen in this quest does, dodging three separate points where it could just as smoothly end. It wants to do everything, and only really succeeds in making Oblivion’s different approaches feel equally arbitrary. The reveal of the feud between Quill-Weave and Arvena is particularly abrupt – especially when the “moral choice” at the end amounts to picking out a prize at the prize counter, which is a common theme. Quill-Weave continues to offer Acrobatics training if you rat her out, so there’s no material loss to siding against her. There’s more here, but it’s all a bit weak.

I want to take a moment to point out how ridiculous Oblivion’s leveled gold rewards are. The philosophy that the same errand should be more rewarding at level 20 than level 2 is a continually frustrating one: bandits using Daedric armor and holding unfathomably valuable magic artifacts, creatures disappearing from the world entirely as you surpass them in power, and yes, getting paid mountains of cash for performing simple tasks. Why should the player receive 600 gold for completing a contract as simple as “deal with a rat problem” just because they’re level 25? How can you feel like a rookie Fighters Guild recruit when you’re receiving 6x the standard payout for grunt work? Oblivion wants quests to feel “rewarding” no matter what they are and when they’re completed. Foreshadowing? Probably not.

In both cases, we’re left with two quests: one short, one long; one simple, one subversive. Neither are theoretically significant beyond enrolling you into a faction questline, though Oblivion‘s is obviously the bigger errand. If it seems like I have a surplus of criticism for the latter, it’s largely because Morrowind‘s approach is so simple as to be exactly what it is, whereas Oblivion is filled with systems that continuously sabotage its innards from within. Again, probably not foreshadowing – stop being so accusatory.

Here’s the kicker: is the Oblivion quest better than the Morrowind one? Most people would probably say yes because, well, which quest would you rather do? The Oblivion one sounds neat! There’s a funny setup, a mystery to solve, some espionage, and a choice at the end. The quest is longer and feels more involved, but that’s a good thing, right? What could possibly be better about killing three rats and then walking away?

A more penetrating question might be: are the Oblivion quest and the Morrowind quest both trying to do the same thing? I would say no, because they derive from two different schools of design. It wouldn’t actually be that hard to create a quest like A Rat Problem in Morrowind – there are quests like it scattered all over the game, especially in Tribunal, where they had more time to focus on them. It’s the kind of quest you design when you’re focused on designing quests, which is a process that tends to elevate “quests” to a higher, emphasized degree of expression.

Chiefly, quests in Oblivion tend to be their own little dramas. They set aside a stage, pick out some actors, and play out scenes until the curtains draw. I’d liken this bespoke, histrionic-driven approach to quests as designing by soap opera. They’re memorable, engaging to watch, and in isolation, supremely fun.

Oblivion is so preoccupied with your unfettered ability to access important locations that it offers immediate fast travel to every major settlement (and quest hub) in the game as soon as you walk outside.

They’re so fun, as a matter of fact, that they have a tendency to shape the container they occupy, subsuming elements of the game that get in their way. Oblivion is when games among the RPG ilk of The Elder Scrolls really began to move wholesale towards designing around precise quest markers and immediate fast travel – in contrast with the systems-driven fast travel of Daggerfall (financial planning) or Morrowind (learning how to use the bus), both of which which involved considerations beyond clicking on a map and teleporting to a destination.

Oblivion is full of catastrophic domino effects created in the pursuit of elevating Questing to a player’s highest concern. It set a standard for NPCs that would move, travel, eat, sleep, and generally try to “live” whenever they could. This made for more “organic” characters than Morrowind, but created a problem: a person you’re looking for might be on the street, in the tavern, or travelling towards a completely different city. This necessitated the quest marker, which always points towards your next objective; this necessitated knowing exactly where you should be going at all times, from step to step, casting anything between any given step as a block of dreary non-time.

But what if the marker is far away, requiring unbroken travel over a sizable distance? “That’s not questing!“Oblivion cries. Being too frightened to push the issue further, it gives you the instantaneous ability to teleport yourself wherever (or close to wherever) a quest decrees your presence. This should highlight its fundamental philosophy: time spent travelling, searching, and generally not standing in front of a green arrow is, ultimately, time spent not questing. Sure, when you’re standing in front of the green arrow, you’re probably having a good time. But between green arrows? Usually, Oblivion is too scared to find out.

There’s a shift from questing as an activity held in reference to the world – quests as spatial interaction, involving meaningful micro-interactions that aren’t “part” of a given task – to quests as a process of getting from state A to B to C to D or E, following the little marks on your compass until you’ve formally completed one and received a payout. They’re little themed attractions in the province of Cyrodiil that seem designed, tacitly or otherwise, to draw less attention to Cyrodiil.

The truth is that it’s probably making a wise assumption about the experiences it can and can’t support. By now, it should be clear that talking about any aspect of Oblivion invariably points back to the crooked timber they built it on: NPCs wander around having ChatGPT conversations in a town square just barely distinct from another; renewing locations continually scale with your level until even the smallest cave contains endgame fights and loot; bluntly, quests have started getting really involved because nothing can mean anything without them. This is a world that’s larger than Skyrim with less to see than Morrowind. Cyrodiil is handcrafted inasmuch as it isn’t Iliac Bay in Daggerfall, but walking through either makes them seem pretty analogous – save that Daggerfall has more interesting terrain.

When vast swathes of your world feel like they were produced by someone who was asleep at the wheel, why walk anywhere? Why not just go from guided marker to guided marker, listening to funny dialogue and swinging your sword until the ennui sets in? Oblivion‘s elevation of the Quest to a point of supreme expression came at a cost: a listless, bucolic Nowhere Land dotted with arbitrary activities supplementing a pile of sometimes fun, sometimes overemphatic errands delivered with increasing desperation. Thus, quests are load-bearing; NPCs loudly discuss them or run up to you and stuff one down your pants. When a location runs out of quests, it loses what little intrigue it has.

This proves, fatally, that quests are Oblivion. The resulting experience is uneven and creaky. It starts to feel like an empty meal you’re swallowing until the next batch of calories arrive – you can find them at the green marker, so teleport quickly before your stomach gets bored.

If quests in Oblivion are fundamental, then I’d refer to quests in Morrowind as supplemental, rather than purely simple. They might not sound interesting on paper, but they are interesting in practice, since Morrowind is an interesting game set in an interesting world filled with interesting writing. They exist to facilitate compelling interactions with the setting, its history, and the characters within it. It understands that go here, kill this, do that is, by itself, not an effective way to produce its effect – an effect, mind, that would be even further reduced if “kill three rats” was a GPS location you teleported to without any regard for place or time.

Rather than papering over its limitations, Morrowind both embraces and subverts them. Consider that both of our rat quests are, contextually, an expression of banality – killing rats is shitty grunt work for new Fighters Guild recruits, who occupy a consistently menial role in a setting like Vvardenfell compared to thieves or mages or even assassins. It is not an exciting venture or a dangerous plunge into the unknown. Morrowind embraces the idea that sometimes a job is a job, rather than treating banality as an intrinsic fake out; Oblivion is so intrinsically banal that it’s rightfully worried you’ll get bored under the same circumstances. It “remixes” the errand, as it often does, filling it with Steps and Surprises and Twists as to outrun its fear of a player deciding they want to be doing something else; a deadly thought in Cyrodiil, where there is, in fact, little else to do.

Morrowind‘s quests exist in a structure designed to point back to itself. Their complexity rarely lies in being long and heavily scripted, but often exists within the context they occupy. While Oblivion‘s quests invariably suggest its shortcomings as a narrative RPG, Morrowind often uses them to point towards depth that already exists.

My favourite example of Oblivion’s uneasy relationship with subversion is the Dark Brotherhood questline. An assassins guild is an intrinsically exciting occupation whose quests have every reason to be filled with twists and turns. Oblivion starts out strong: the bit where your boss tells you to kill your fellow Brotherhood members is a great one. Hot on its heels is the next twist, which is that someone is replacing your orders with alternative objectives, tricking you into killing other members of the Brotherhood. Okay… then your fellow Brotherhood members proceed to kill your boss while you’re not around. Then the traitor reveals himself, kills two Brotherhood… okay, so there’s one twist that they just repeat over and over. It’s like they’re too anxious to trust that the quests are interesting by themselves, but not so anxious as to think of another way to draw the player’s attention forward. Pictured: not Oblivion. Sick of looking at it!

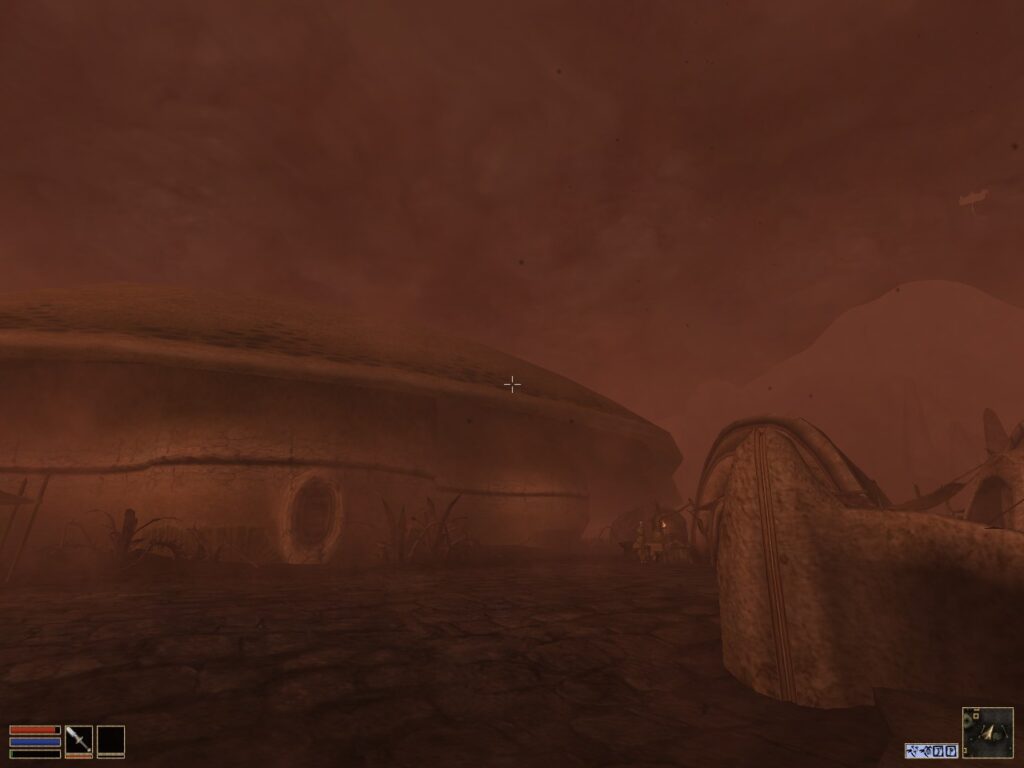

An all-encompassing example is found in commuting around the map; bereft of convenient fast travel, getting from one place to another becomes half the process of doing anything. A simple task might require you to learn the layout of a new city, or puzzle through the quickest use of local transportation to get from Khuul to Caldera, or follow precise directions like “turn left at the hill until you hit some trees, then…” to reach a particular location. Being asked to visit the Foreign Quarter in Vivec to visit a particular shop and speak to the owner is, itself, an interesting experience. I spent hours in Vivec alone doing as many quests as I could find – seriously, Vivec is fucking huge. Learning how to navigate that city, demystifying its layout and feeling less like a perpetual tourist in the process, brings as potent a sense of progression as raising numerical skills.

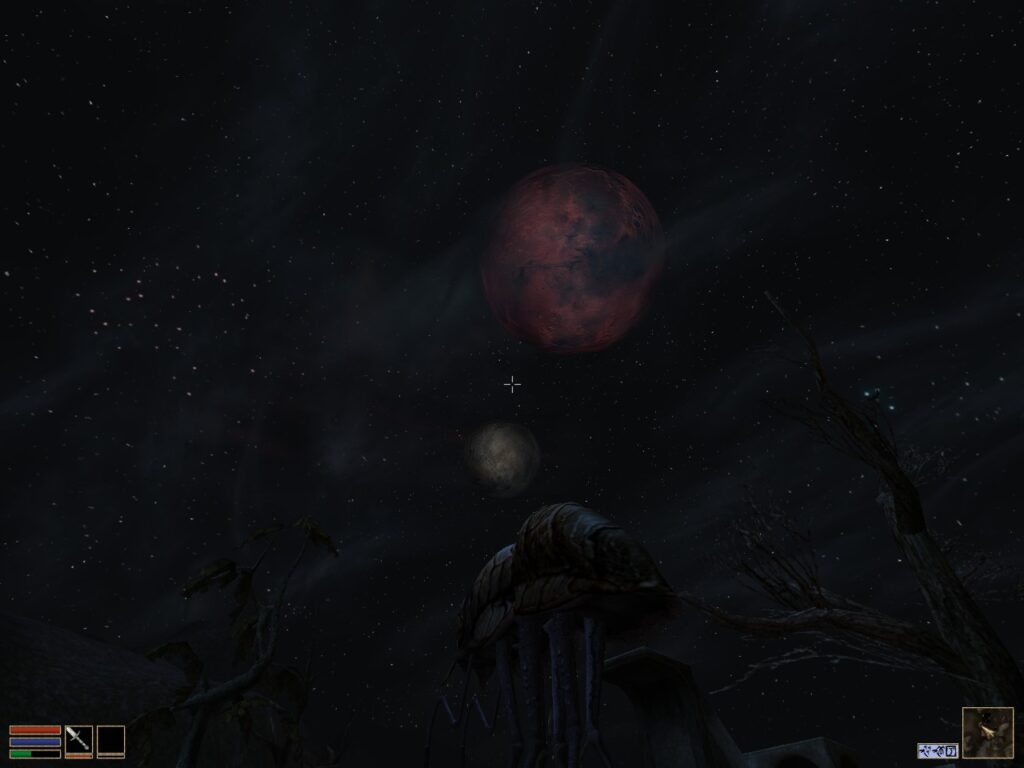

These things matter! By building a road and then requiring you to use it over and over, Morrowind facilitates a dialogue with the world itself. That dialogue occurs whether you’ve been tasked with shopping, ripping someone off, or even killing a demon – all of these things are themselves representative of the spaces and forms they occupy, sometimes together, sometimes apart, and they rarely need to be more than they are. Look closely at each, and you’ll see a grain of Vvardenfell.

This greater emphasis on quests as conduits amounts to a looser treatment of the quest themselves: they can be long or short, simple or programmatically complex, straightforward or circuitous. Less of a push is made towards tracking them, with the journal hardly discriminating between completed and ongoing tasks. This means that you might forget about a minor favor you’ve been asked to do, or you might think you’ve “completed” a task without actually finishing it; you might pawn off the package you’re intended to hand to Caius and effectively sell your entrance to the game’s main plot, or you might wander around the map sightseeing without ever starting anything at all, and Morrowind understands that this is completely fine. Fulfillment feels equally portioned along every coast, and no matter what you do or how long you do it, you’ll almost certainly walk away happy.

Morrowind is a game of quotidian joy, which means that quests are less individually expressive but infinitely more simpatico with the raw act of playing Morrowind. Many of them strike excellent balance between simple tasks and evident hand-authoring, which engages the feeling of experiencing somebody else’s art without invoking the myopic Content Trough that became “radiant” quests in Bethesda games like Skyrim and Fallout 4. The culmination of this trend was Starfield, where the world itself is a radiant quest that never ends – a malaise only scattered, of course, by the quests that provide the necessary framework to embed meaning into anything you’re seeing or doing. Those games saw “simple quests” and decided that “simple” meant “simply don’t design anything,” devaluing everything around them until the world itself became less significant than the vignettes it contained; where the only real quest, in tragic prescience, is to identify whether something was produced by a human or delegated to a computer.

It’s difficult not to see these things germinating, latently or otherwise, in Oblivion. It’s no secret that Morrowind was a singular, one of a kind effort from Bethesda; there’s certainly never been another Elder Scrolls game like it. While Skyrim was far less shaky – shakier in some places, especially its factions and cities, but at least within a map that didn’t feel pointless – it still remains distant from embodying what I enjoy: places that feel realized, filled with opportunities to learn, dotted with things worth seeing down roads worth taking.

I want to roleplay around an existence, rather than watch existence roleplay around me. For that, I’ll have to keep coming to Morrowind, where the most potent fantasy is one of life itself.

I got really into Morrowind and, henceforth, I’ll be blogging about Morrowind until I’m sick of it. I’ve got at least two other sections of a larger article that I’ve split into chunks, so expect at least that many more of these. The next one ideally covers an important point, which is that Morrowind’s quests and their respective progressions are often more complex than subsequent examples despite their relative staticity. Consider it “Part Two” of the argument made here.

Next time, I’ll be breaking down Morrowind’s brilliant approach to factions. To quote the Sermons of Vivec: The ending of the words is CHECKBACKBIMONTHLY.