There’s a scene in Alien: Romulus that, with little else to remember, will probably serve to define it. Near the film’s climax, the synthetic Andy – the movie’s true star, brilliantly portrayed by David Jonsson – gets his Big Moment. As his surrogate sister is nearly killed by a pouncing Alien, Andy leaps from a massive elevator shaft, rides the Alien’s flailing body to the bottom, and slaughters it with a decisive hail of gunfire. It’s the culmination of a movie-long arc: The first glimpse of extrication from an existence where Andy can escape the shackles of being viewed as an eternal child without reverting into obedient corporate property; the first step towards the end of a journey that may, one day, see him find the capacity to live for himself.

… And as he stands over the Alien’s corpse, he says “Get away from her, you bitch.” From Aliens. Spoken with a slight stutter, to elicit laughter, and flanked by a pregnant pause, to elicit cheers or clapping or maybe just any response at all. I’ve heard of a few theaters breaking into rancorous applause – for Aliens, not Andy. It got a handful of uncertain chuckles at my screening, as if nobody really knew what response was appropriate. I have to wonder if they, like me, were left paralyzed by their own confusion: What? Why’d he say that? Would he say that? How did we get here?

The line is terrible for a dozen reasons which are largely self-evident: It’s awkward in a blunt and shameless way because it’s not something he would say, it’s meaningless (is the film suggesting that Andy has watched Aliens?), and it immediately causes you to start thinking about the climax of a better, more considered movie. A movie that was quoted, rather than a movie that simply quoted.

But worst of all, the line makes the culmination of Andy’s journey – itself all the movie really has going for it – a container for an Aliens reference, bound only by the tenuous connection of both scenes depicting someone fighting to protect someone they’ve come to view as family. Compare both scenes, however, and their distance is apparent. In Aliens, the line underscores the beginnings of a climax, tinged with triumph and laced with desperation, a plea morphed into a command; in Romulus, Andy says the line after he’s already succeeded in killing the Alien, delivering an empty gesture over a body that’s already dead. Devoid of drama, uncertainty, or life.

Alien: Romulus is this moment writ large.

There is one thing that can be said is unique to Romulus: it is the first Alien movie (Predators in absentia) that is simply not interesting.

However you rank the original tetralogy or Ridley Scott’s prequels, their one commonality, beyond all divisiveness, was that none of them were empty. Whether you disliked Alien 3, Resurrections, Prometheus, Covenant, or even Aliens, it was difficult to argue that any particular entry was just… devoid of even a single, uniquely compelling thought or image or thing. I would say Alien has a pretty good batting average! But more importantly, even the most clear-cut stinkers were something. There’s a ton of good shit in Resurrections, and even before I came around on Prometheus, it was still full of nifty stuff.

Romulus, by comparison, is a box filled with things from previous Alien movies. Remember Ash? Remember the Colonial Marines? Remember the black goo? Fuck, remember the Newborn? This Alien movie does, and it’s going to make sure you do, too. For the first time, instead of each Alien film taking us to a radically different place, we find ourselves in a place we can recognize both instantly and intimately – fans of Alien: Isolation will even recognize the game-saving telephones mounted on the goddamn walls. It’s Sevastopol Station, again. Even the fourth act twist, which threatens to broach new territory, is lifted almost wholesale from Resurrection. If you see something you don’t immediately recognize, make sure to look twice – it’s probably just from Alien 3.

Romulus is a movie built out of other movies, and because those movies were generally good, Romulus is competent. It’s anodyne. It’s a clip show, or a greatest hits album. What are we going to say about it? Conversations around Alien 3 often touch on the innate cynicism of franchise filmmaking and the harsh reality of shoving a story forward until it can only end in tragedy; conversations around Prometheus and Covenant touch on the nature of God, the distortion of iconography, and the recurring theme of antinatalism that embeds itself into even the most inoffensive Alien material; conversations around Romulus have mostly revolved around questioning whether it’s pretentious to feel dissatisfied and a little disconcerted by a proliferation of key-jangling that’s increasingly legitimized by defensive key-jangling enthusiasts.

Alien movies have always been defined by the risks they take; Romulus exists in a bizarre (and increasingly common) lineage of legacy sequels that take risks to avoid taking them, to entertain through pattern recognition. Quoting other Alien movies, for instance, or leaning on structural parallels to previous Alien movies, or maybe just trying to bring someone back from the dead.

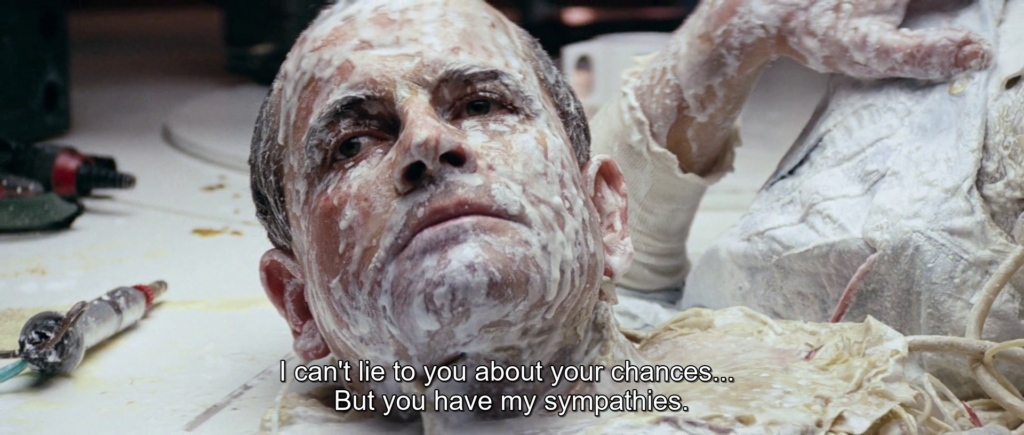

Sir Ian Holm, the actor who played the synthetic Ash in the original film, is “back” in Romulus. He “plays” the character of Rook, ostensibly a different android from the same line of models, hence their shared appearance. You might infer from the end of the previous paragraph that a minor roadblock presents itself here: Sir Ian Holm is dead. He passed away in 2020 at the age of 88, long before Romulus was in production. Audiences can be assured, however, that nobody is ever really gone – Romulus features an “AI” reconstruction of his face and voice circa 1979, allowing him to “play” the “character” even though he’s “dead”.

Much has been said about the ethics of the technology used to create Rook, but much of it should be obvious to anyone with a soul: bad, morally repulsive, ontologically evil. An insult to life itself. Rarely has a studio film felt so shamelessly traitorous to the entire human race. Watching Holm’s repulsive deepfake cavort around on the head of a legless torso is the most disturbing imagery to appear in any Alien movie, so of course the film treats the ungodly visage with unrestrained glee – it’s a bit like watching someone abandon a child to fawn over a chittering centipede.

It’s like a skinsuit that an escaping ReBoot creature would fashion from one of its victims.

Perhaps this sense of pride, more than anything, is what makes this horrifying monster so hard to observe. Working around the absence of deceased actors is nothing new. Rarely has this work produced anything good or satisfying – death isn’t satisfying, generally, nor does it look good. To see a character portrayed exclusively through discarded material or behind-shots of a fake Shemp in a wig or a hasty recast is, ultimately, a depressing exercise and an unlovely reminder that people go away.

Things got worse with the introduction of digital effects, which brought along a specimen of false confidence that It Could Work and Maybe Nobody Will Notice. When Nancy Marchand passed away in 2000, The Sopranos could’ve simply had her elderly character die off-camera, which they did… after attempting to produce a “final scene” out of deleted takes and awful, awful CGI. The result is jarring, ugly, and a terrible final note for her incredible performance – an uncanny digital doll sputtering out awkward, disconnected lines to a physical actor yelling at a wig in a chair. The effort cost $250,000, was a sad mess that audiences instantly deplored, and is universally remembered as one of the worst moments in the show.

Would it look better today? I guess. Would it be good? Absolutely not. At best, it might trick particularly unobservant viewers into thinking Nancy Marchand had filmed one final scene for The Sopranos, which, like… she already did, but that’s beside the point. The reality is that Nancy Marchand was a brilliant actor, and actors aren’t VFX puppets reciting random lines; her character had to die when Nancy died because Nancy is that character. Of course we didn’t want her to die, but she died. Dead people are dead. No amount of time or technological advancement makes wishing on the Monkey’s Paw a valid solution to an eternal problem.

At least you can say that, bizarre little experiment that it was, nobody wanted to keep her character without keeping Nancy through a perpetual ritual of sustained digital necromancy. Nobody wanted to start kicking audio together until Nancy could deliver “new” lines. In the end, nobody wanted to make it at all; like many similar projects of its era, it was made anyway, and at a comical level of expense. All to create a sad, impotent little knock on the coffin of a person one had to accept would never act again. But at least one could understand that, one way or another, The Sopranos was in a difficult situation to which “trickery” was a rationally appealing option. It was obviously not a decision made lightly or enthusiastically, and even if it was the wrong decision, everyone involved clearly knew it by the end.

Stills from Disney’s new sci-fi horror movie titled “The Tarkin Abomination”

With Disney… Disney delights in this. They do it avidly, gleefully, and largely without cause. This method is their first choice, and has been since Rogue One graced the world with some of the most expensive zombies ever dragged vacantly through a movie. They want this. They actively seek out opportunities to do it, not as a response to actors dying but precisely because they’re dead. Because audiences accept what becomes standardized. Because the resulting ghoul is a fun little VFX toy, and because Disney, ultimately, wants to create the precedent required to own an actor’s likeness in perpetuity: Why hire human beings when you can encase them in digital amber, fire them, then control their bodies and voices at will? Why pay an actor’s salary over a long period of production when you can cut the books down to only paying the salary of the (notoriously non-unionized and underpaid) VFX workers responsible for summoning them at will? Why respect death if you don’t even respect life?

Beyond a good human’s gut response to this rancid freak of nature, it’s important to understand why they’ve done this. The impetus to normalize this is more important to Disney than Romulus itself. Whatever role Fede Álvarez, the film’s director, had in making this happen is ultimately ancillary, though this does nothing to absolve him of personal responsibility. He’s just excited to play with an action figure, which is precisely what Corpse-Holm is. Its role in the script is exactly what you’d expect from a digital monster that doesn’t need to exist; there’s fundamentally no reason for Sir Ian Holm to be here, and the film is actively worse for ignoring this fact. At the same time, he’s the only face from the original film who could technically be here, which is the answer to the question posed by the excuse. To reiterate, Sir Ian Holm is here because he’s dead. A significant role in a noteworthy blockbuster being played in multiple scenes by an actor who died before he ever heard the words Rook in Alien: Romulus is simply the next link in a chain – one that culminates in still-living actors being paid a diminishing pittance to exist as all-digital clones in movies without ever being offered an actual job.

I’m also unmoved by placations that they “cleared it” with his estate: this is a false dilemma, though it speaks to a particular horror of our time. That this was possible thanks to a headcast of Holm produced in good faith during his work on The Lord of the Rings movies, when he was a living human unable to offer his consent (or lack thereof) to that data being utilized by nascent technologies that simply didn’t exist yet, is a terrifying thought. I don’t know anything about his family, and I won’t make assumptions about them or their judgement. But, as far as managing a loved one’s estate goes, isn’t “we’ll pay you a meaningful amount of money if your stamp of approval goes on us hooking an image of your dead father/husband up to a computer so it can recreate a vegetative, sclerotic image of his eternal soul” a pretty mortifying situation to find yourself placed in? Does every performer’s immediate family need to deal with this forever? What if they refuse and there’s enough legal precedent for the studio to just… do it anyway? What if they stop asking?

The “character” of Rook is just Ash – pictured above, since I couldn’t be bothered to track down a camrip. I was initially under the assumption that it was literally Ash, somehow scavenged from the Nostromo and rebuilt with some form of memory loss. Nope! Same model of robot, which functionally means that Rook is just Ash. It thinks like Ash, has the same desires and protocols as Ash, and fulfills the exact same role as Ash: The duplicitous company stooge who views human life as useful until the precise moment it can be thrown away (lol). If that wasn’t enough, the number of scenes where it just quotes Ash – creating the hilarious idea that Ash in the original movie was like Woody from Toy Story and had a list of Programmed Iconic Phrases – can lead nowhere but a miserable non-character who has no separate identity and, without a breathing actor at the helm, no identity at all.

Also, it looks terrible. Did I mention that digital clones of dead actors still look terrible? I think they’ve actually gotten worse. This is less important than the inherent moral rancidity of the technology and the forces driving it, since it could start looking better at any time. But, for the record, the result still looks like shit. It’s almost impressive to see such an immense amount of money and manpower spent towards somehow utilizing the one piece of digital effects work that makes a malfunctioning robot look less convincing. One could imagine a living Sir Ian Holm transforming the role into something worth viewing, since Sir Ian Holm was a great performer; Holm, in case you missed the news, is dead, and the presence of his vacant simulacra in Romulus is a portent of dread that overshadows anything in the actual movie.

Watching Romulus, having run out of other things to be thinking about, I was reminded of a chapter from Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities where he considers a “dead” city, that of Adelma:

I thought: “You reach a moment in life when, among the people you have known, the dead outnumber the living. And the mind refuses to accept more faces, more expressions: on every new face you encounter, it prints the old forms, for each one it finds the most suitable mask.”

…

I thought: “Perhaps Adelma is the city where you arrive dying and where each finds again the people he has known. This means I, too, am dead.” And I also thought: “This means the beyond is not happy.”

It conjures the image of a caliginous, empty city. A place unable and unwilling to imagine new faces, decaying stagnantly. A world that’s silently full and loudly empty.

When did movies like these start feeling like the enclosure of the frontier? When did all these direct-to-streaming daubs, remakes, legacy sequels, and relentless content troughs start to feel almost tauntingly vacant? As if they’ve gone beyond inoffensiveness and become almost territorially dull, like snarling animals staking their turf. What message gets communicated when you’d rather spend millions recreating the image of a dead man just to circumvent hiring an actor who’s actually alive? It’s creatively lazy, but it’s not materially lazy. At this level of vapidity, an intense amount of labor goes into maintaining the simple absence of new ideas. But… why? Even with everything I’ve said, why?

The studio system that once enabled a film like Alien busies itself now, like back then, with enabling paradoxes. To briefly speak an empty language, Alien is a profitable and well-loved asset that came about by letting a bold filmmaker take bold swings in the direction of the New. The result has, over time, generated well over a billion dollars in revenue; the takeaway, however, will never be that letting the bold filmmaker take bold swings is good or profitable. Instead, the success of Alien merely tells executives that Alien is a Valuable Intellectual Property, discovered by shrewd businessmen and extracted from the ground like gold or petroleum.

A love of money doesn’t trick executives into funding new ideas with the potential to generate profit – not like it used to. Alien, much like a disturbingly large amount of things, was only financed because Star Wars was a massive success. Fox wanted to release more sci-fi movies as quickly as possible, and because Alien was the only sci-fi script on their desk, it got made. Think about how many people passed on Star Wars. Fucking Disney passed on Star Wars, then swooped in later to buy it after other companies had taken all the risks for them. Would anyone bankroll it now, even if it flitted across the studio system tomorrow with an established director? I’m confident in saying absolutely not.

Alien was only made because Star Wars was made, and Star Wars was only made because a handful of bigwigs at Fox actively shielded the movie from cancellation at every turn. Did their efforts make an impression when Star Wars became a multi-billion dollar enterprise? Beyond convincing a board of directors that profitable movies had spaceships in them, not really. Did the success of Alien tell them anything? Nope. In fact, here’s the kicker: even when the film was a visible success, Fox lied about it.

Alien cost $11 million to make and grossed at least $78.9 million by the end of its first run. For anyone who isn’t a math whiz, $78.9 million minus $11 million is about $67.9 million bucks. For a few headache-inducing reasons, that doesn’t mean the film had grossed exactly that amount, but it certainly amounted to a predictable number of zeroes to be divvied among the usual parties. It would not, per the laws of known mathematics, come out as a negative number.

In a classic case of Hollywood accounting, Fox insisted on a loss of $2 million in 1980 – a number so fucking ridiculous that a resulting outcry from industry accountants happened to coincide with Fox finding an extra $6 million under some cushions. That meant Alien had actually generated a profit margin of $4 million… which was also plainly a lie. Changing their story at all was an admittance to the lie, but changing it to another lie was embarrassingly rapacious – in other words, classic Hollywood accounting. If Alien was a failure, it meant that whatever money it made was likely to stay with Fox. Even better, it gave Fox a great excuse to cut further spending on the Alien IP. Why fund another movie when you can reap short-term gain?

Brandywine, the studio that actually made Alien, had to drag Fox to court over withheld profits; the lawsuit took years and, so far as I know, didn’t result in anyone at Brandywine getting what they wanted… except for Fox agreeing to fund a sequel. The idea here seemed rather magnanimous: Brandywine could recoup the money it was legally owed by… uh… making another movie for Fox, more than likely receiving the same (small) cut that Fox had just loudly slithered out of paying.

All of this kicking and crying result was a modest little success named Aliens, which only grossed around $157 million worldwide. That number is from Fox, so feel free to assume it made way more. After everything, Fox was ultimately punished with an extra $100 million bucks. That’ll teach them a lesson!*

*It won’t!

The film industry, as with all industry, has been a nightmare from the moment of its invention; in the last few decades, as with most creative industry, it’s become materially and significantly worse. All actions taken are taken atop a platform of bones, which amount to continued financial success built entirely on decisions that will no longer be made. The available materials for generating more profit are purely the materials which have already done so – inbreeding is preferred, so long as nobody questions how anyone got here in the first place. With every passing year, it becomes harder and harder to imagine the largest companies supporting and distributing, even inadvertently, a small portion of original art.

If Romulus points towards anything, it’s a world where Alien and anything with its ambition can only exist if it already exists; a world where you better have found a way to trick the studio system into bankrolling whatever real idea you had before all the loopholes were closed. And if you did, here’s your reward: the legacy sequel. A shambling, rotting thing that exists to patch up the cracks through which your own idea once squeezed – the same art that was dismissed and distorted by the same companies who reaped all the benefits later. Success, like failure, is just another way to get sucked dry.

The startling newness of Alien has been suppressed, commodified, and junked. It has been made to ensure that, paradoxically, nothing like it will ever be allowed again. These unseen and unspoken possibilities – filmmakers whose greatness will never be known, though it would be exploited if it ever was – have been robbed from a list of possible futures. The culprits are moneymen and the systems of moneymen: they who no longer care about producing any future so long as it can be substituted for a stagnant, deteriorating past. Or, as the godless necromancy puppet of Ur Ian Holm would describe it: A Perfect Organism®… Unclouded by Conscience™, Remorse™, or Delusions of Morality™.