Edward Gorey once said that there was “probably no happy nonsense,” and I’m inclined to believe him. Things that don’t make sense are, by nature, macabre; vanitas of the mind and soul that harshly present us with the death (or possibility thereof) of sensorial mooring. Nonsense is an offense, and things that are crooked cannot easily be made straight – likewise, fear comes from the realization that such grim absurdism hides not in remote experiences, vague happenings, or baleful childhood nightmares, but in material fact. In a forest, as in a city, as in a house.

Thief: The Dark Project is full of frightening visitants and ossuary ghouls; nearly half of its missions delve into plainly supernatural or inhuman encounters, from Down In The Bonehoard to The Haunted Cathedral. Secondary only to stealth in Thief is horror. And yet the scariest mission in both The Dark Project and the trilogy at large – yes, Robbing the Cradle included – takes place in neither a crypt nor a haunt, but in something different.

Very, very different.

Nothing about The Sword sets off immediate alarms. Garrett’s briefing tells us that he’s been hired to steal a magical sword from an “eccentric” nobleman named Constantine, who dwells in a manor of his own design near the edge of the city. Garrett has very little information to work with – the house was built so recently that our map of the baronial estate is drawn from observation and hearsay. Beyond a tinge of unease germinated by the description of the mansion’s layout as confusing and maze-like, there’s little to suggest a deviation from routine.

The Sword hinges on the successful execution of a trick. More than many of the objective-focused stealth games that followed in its footsteps, Thief is always about tricks; a stated goal or target can rapidly shift into something wholly unfamiliar, sometimes mere seconds into a mission; treasure can be found missing, potentially turning an entire heist into a red herring; even maps, typically trustworthy even at their most diegetic, might be incomplete or out of date.

But The Sword has a new trick: through all of this, one of Thief’s lone constants has been that the places you slink through make sense. Human hands have built them, sometimes with alarming compartments or an unusual sinuosity, but never in a way that rejects human visitation – your mere presence is not alienating, as in animal burrows or dreams. After two previous mansion-focused heists, there’s little doubt that Thief is a game that can build a house. The same impression is conveyed by our first glimpse of Constantine’s manor, which is fairly unassuming. There’s no suggestion of a break in convention… save a window, left slightly and portentously akilter. An omen of things to come.

If the eponymous asylum-turned-orphanage in Robbing the Cradle was a house with bad dreams, then Constantine’s manor is a house on whom the Russian Sleep Experiment has been particularly unkind. The pace at which you discover these aberrations depends on how you delve into the manor itself; the first floor, which you’re funnelled into, suggests the first threads of irregularity. They centralize on the ceiling like liquid leaking through a floor, from doors built sideways – peak your head through to hear calliope music playing from a source unseen, only to clarify it has no source when you reach it – to gulfs created by the layout of the hallways above.

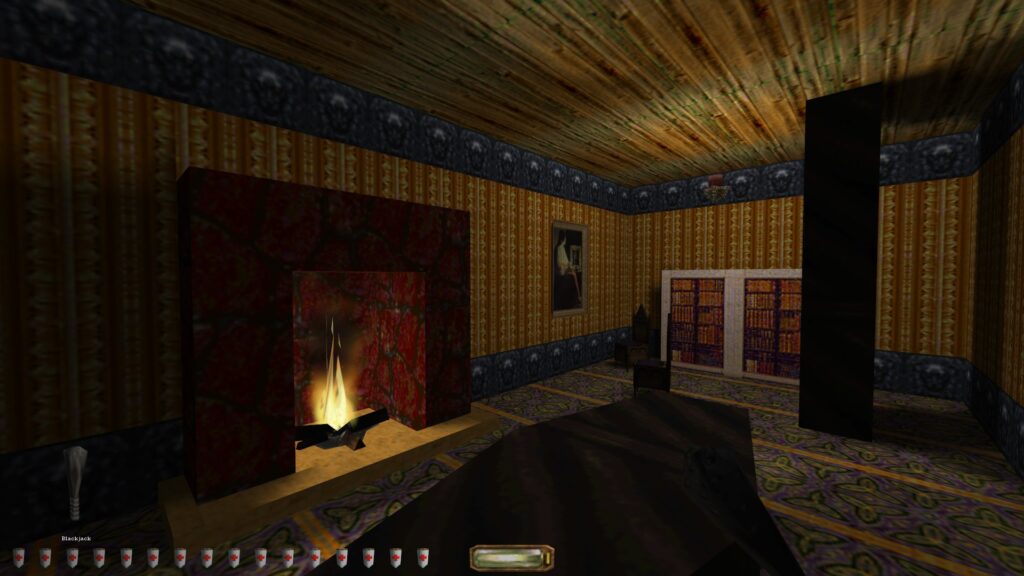

Structurally, the house is both suitably baroque and strangely spartan, driven by the tastes of a proprietor who, unlike your previous targets, lacks a clear sense of opulence or decorum. These lower rooms, themselves the most “inhabitable” of the entire building, feel starkly unfilled; tables with no food served from a kitchen you can never find. The Sword lacks servants, with their expected presence and eye-rolling banter. It is an unhomely house; even the fireplace feels cold.

It’s remarkable that The Sword, far from simply being a collection of weird rooms, manages to twist the established rhythm of a typical Thief mission. While previous manor heists provided a reasonable division of “soft” and “hard” surfaces – soft surfaces allowing you to move without being heard while hard surfaces give you away almost immediately – Constantine’s mansion features an extremely uneven selection of floor types. This main hall requires a strange prance-like motion to traverse without making noise, jumping between carpets to avoid cautioning guards. Suggestively, the most common surface you can move along quietly is grass.

There’s an overarchingly subtle absence of typical Thief manor mainstays, not just in servants but in prattling, drunken guards. There are guards, but they have little to say and seem imprinted by the discomfort of their surroundings . Worried, perhaps, that their words will drift through the caliginous and uncertain walls of Constantine’s gift to the world. Garrett is the same, foregoing his typical banter as if in terror or awe. A droning ambience fills the air, haunted by the slightest hint of something whistling in the stale wind.

In the garden, more than any other portion of the first floor, disquiet pervades in lurching increments. It’s a circuitous maze of capacious stone chambers ruled by scattered, almost invasive greenery. There’s just something wrong. I remember first playing this and feeling a jolt of real fear (larger than even my first encounter with a zombie) upon turning into the chapel entrance, with its rust-red walls and howling statues. It was the first time the discomfort of the entire procession came to the forefront of my mind: You’re a thief, and you’re not supposed to be anywhere, but somehow the animal in your brain knows deeply and truly that you’re really not supposed to be here.

Things deteriorate quickly on the second floor, which is plainly not designed for a human being. Holes in the ceiling espied from below become gaping omissions of flooring, flanked by traps that spit fire and magic. Sudden damage or death by a stray ball of energy is an archetypal jumpscare, but less scary than the traps themselves is their place here. You learned the language of these contraptions in the defense systems embedded to protect tombs, and now they’ve been placed within the confines of a man’s house. They don’t even protect anything; there’s nothing at the center of the area worth grabbing. They exist in protracted conflict with the established grammar of Thief, and for no reason beyond, of course, your shock in the face of a brazenly disregarded rule.

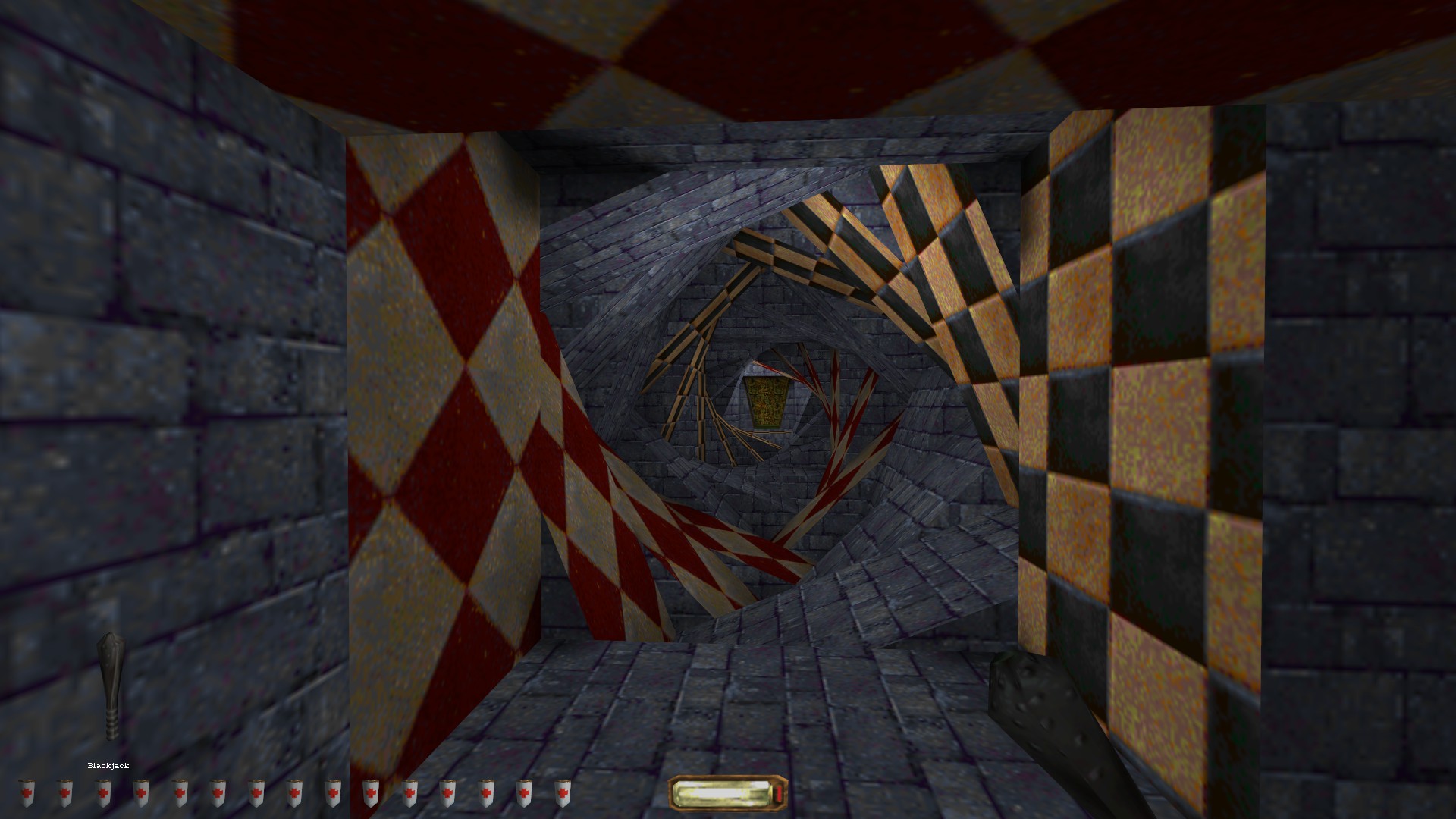

All of this culminates in the third floor: a fractured, taunting collection of preternatural sights and noxiously bizarre geometry. Halls are seen sliced and shifted into masticating hallways of jagged plaster-teeth, stumbled through with drunken bewilderment; a room flanked by disorientating illusions; stairs suspended above an abyssal twilight, so tenuously supported by Thief’s own rendering techniques that geometry visibly flickers in and out of visual alignment. Rooms appear with mismatched textures, upside down, filled with incongruous assets.

The noises. You wander through birdsong and ghostly moans and what sounds like that mewling sound Norris makes in The Thing as its head grotesquely tears itself from its renegade torso. What underlines the ambience of this portion is a persistent giggle: tinny and yet somehow thick, leaving rooms envenomated with distant amusement. It’s like the house is playing with Garrett, whose own ineptitude in the face of impossibility only grows with each door opened. It is a willing, incontrovertible sign that The Sword is laughing at you.

When the eponymous sword actually appears, it spins above the ground like a weapon in a mid-90s first-person shooter – a school of abstract environment design that The Sword regularly seem to evoke, as if returning us to an older world. It’s one final inch of madness before a battered player can descend Constantine’s vertiginous estate and finally skitter into the wan and moonless night. Frightened, made small; a witness to something new.

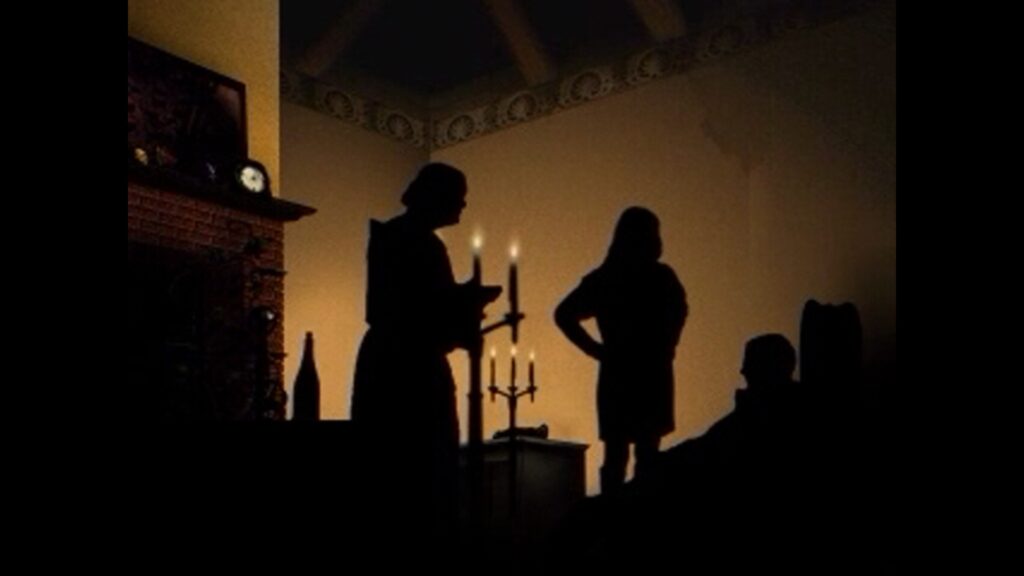

I love The Sword because of what it accomplishes in isolation, but it only becomes better in the grander scheme of Thief. Completing the mission reveals that you were hired to break into Constantine’s estate by none other than Constantine – his total absence even within the depths of his own house, not to mention its moments of startling test-like artifice, are an early indicator of his complicity. Impressed by your abilities and calling himself a “collector”, he commissions you to heist a mysterious artifact in exchange for an exorbitant payment – one that Garrett knows he’s unable to refuse.

This is where Thief picks up its primary narrative arc, which culminates in the reveal that Constantine is actually the ancient Trickster: a scheming, arboreal Pagan god tied to the most primal elements of reality. His estate is a natural reflection of its eldritch and wholly inhuman origin. In the world of Thief, as far as its dominant ideologies are concerned, the unearthly resides within the earth itself, contained in woodland groves and changing seasons and the fruits that grow without the interventions of man. A city is predictable where a forest is not; the flowing river erodes arbitrarily what architects and planners shape with intent.

Constantine’s “eccentric” estate reflects the quiddity of a being whose desired shape of existence has been subjugated by masons and factories. The Trickster is chaos – a great god Pan to whom order is bedlam and structure is an imprecation, whose form shifts disconcertedly around a changing environment shaped from raw materials he can no longer recognize. Far from simply containing an abundance of plants, The Sword is a mockery of man’s world. It subjugates, rather than reconciles, the relationship between a stately house and an arbitrary wilderness; a world of burrows and caves and distant chittering midnight.

Constantine’s manor is horror in the abstract, and the fear it embodies is both spun and powered by its untethering to concrete reality. It is an escalation of an inchoately present force left chancily floating, unrestrained, perhaps able to touch or trap or somehow infect. To be caught by guards is frightening because you do not belong; zombies are frightening because they kill and rot and infect; the manifold monsters of Thief are frightening because an angry animal has gnawing jaws and scraping talons. The Sword is so violently troubling because we don’t know what happens next, either as a consequence of our exposure or as a corollary of its presence.

Structurally, it’s that terrifying scene in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse where the ghost of a woman stands rigidly in the dark before walking strangely and lurchingly towards a man who seems unable to flee – we know something terrible will happen if he’s caught, but what? Something more or less than death? Something else entirely? The scene is slow, the ghost unhurried, every step an eternity to ponder the ramifications of her presence. A scene like the Leatherface chase in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is so affecting because everything from the frenetic camerawork to the panicked acting conveys the full horror of being pursued by a violent and messy end. Pulse, like The Sword, accomplishes this laterally: our inability to articulate that core question of what? is the shard of glass that embeds itself in the brain. Rather than existing in its moment, it follows you to bed.

It’s the dread of watching uncertain things become bent by an uncertain agency to an uncertain end; certain only that they glare, however briefly, towards you. The Sword is nonsense, and yet it remains ideology: a sylvan horror of the primeval world putting into stone and tile what it cannot put into language. This is nonsense as a transfigurative force, and we remain uncertain of the picture we glean from the bad magic it leaves behind.